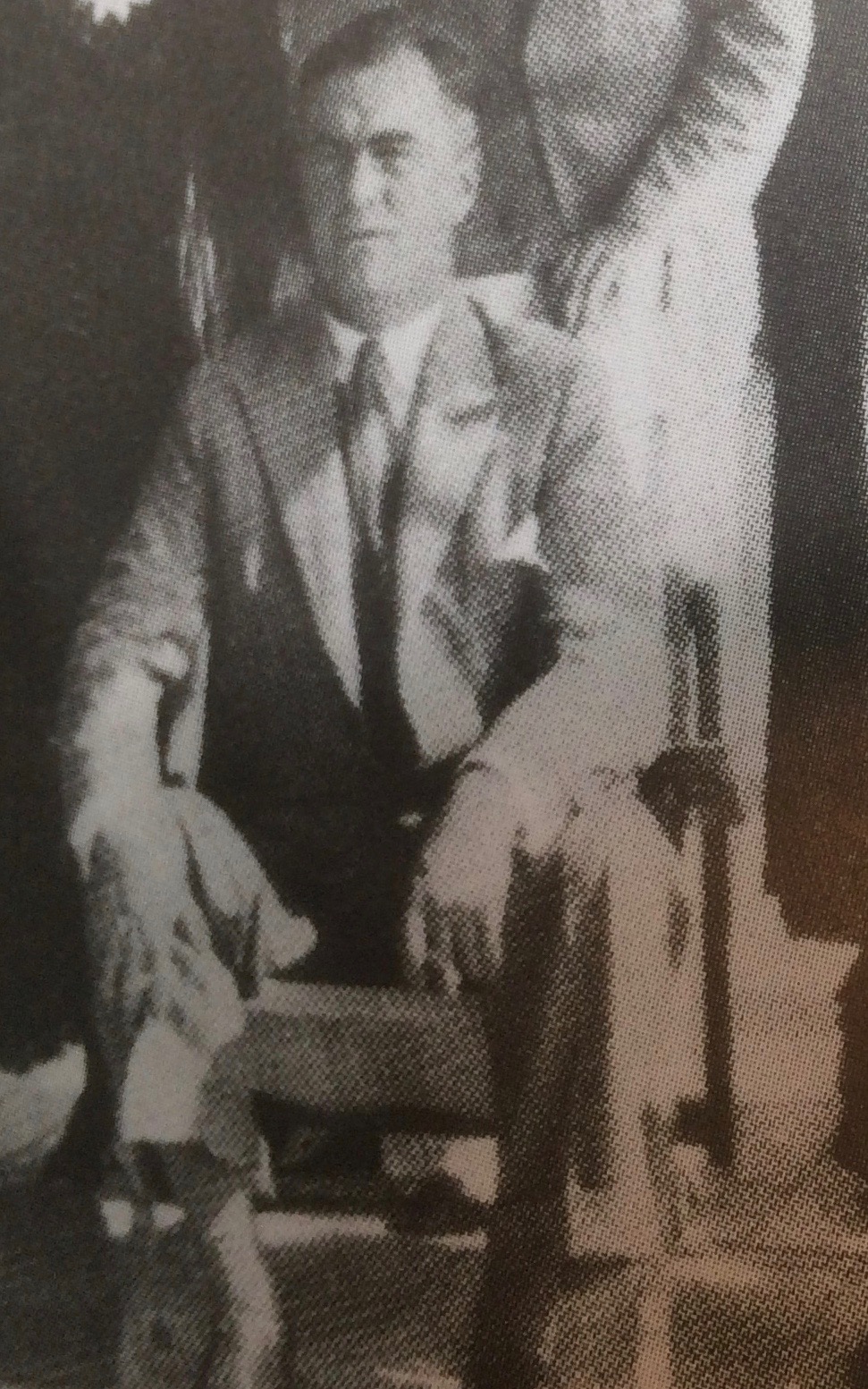

Clive Harold Voss was Australia’s first official trade representative in France. Appointed in 1919 by Prime Minister W. M. ‘Billy’ Hughes, he held the position until the outbreak of the Second World War.

The second of three sons of Ethel (née White) and Harold Dixon Voss, Clive Voss was born in Gulgong, New South Wales. His father, a Welsh migrant, was manager for rural branches of the Bank of New South Wales before moving to Sydney. Clive attended Bega Grammar School, and then Barker College in Hornsby. A noted sportsman at school, he continued to demonstrate his prowess in local cricket and rugby teams when, following in his father’s footsteps, at the age of 18, he began to work for the Bank of New South Wales in country towns and then, in 1911, in Hornsby.

Banking was not however Voss’s vocation, and in 1912 he left Australia for France, with a view to becoming an aviator. He later claimed to be the first Australian to gain a French pilot’s licence, and it was through a joy-ride over Versailles that he met his future (French) wife, Georgette Geffroy. They married in Canada in April 1913, and over the following years had two sons (John, b. 1915 and Michel, b. 1921).

In the First World War, Voss enlisted in the British army and served in the transport division, rising to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. It was possibly in his role as driver during the Paris Peace Conference that Voss met Australian Prime Minister William (Billy) Hughes. Hughes’s decision to appoint a trade officer to France was one of the few recommendations of the 1918–19 French Economic Mission to Australia to be acted upon—it was very much convergent with the Prime Minister’s vision of greater Australian independence in international affairs. Until that point, Australian commercial interests in France (and more broadly on the Continent) were handled by the British Chamber of Commerce. Voss set up his quarters in the same building the British Chamber occupied in the prestigious rue Halévy, but made his space distinctively Australian.

The appointment proved to be extremely controversial. Although Voss had banking experience and a good knowledge of French, his competencies for such a post were glaringly limited. His colleagues at the Australian High Commission in London, Henry Braddon and Walter Leitch, were not slow to point this out, and it took direct intervention from Hughes to prevent Voss from being dismissed in 1920. Over the following decade, both Voss and the Paris office were under more or less constant attack, and while Voss was far from passive in defending his achievements and the prestige value of a specifically Australian trade office in Paris, what saved the operation from closure was almost certainly more its low cost than any strategic value successive Australian governments saw in it.

Voss’s communications with the Australian authorities show not only enormous good will and energy, but very considerable communicative and networking skills, and a very sound understanding of French governmental and regulatory practices. In relation to trade, he organised scores of individual contacts between French and Australian business concerns, and provided responses to a constant flow of questions about Australian customs regulations. He quickly understood what the impediments were to increased commercial relations between France and Australia: namely, the huge balance of trade discrepancy in Australia’s favour, and Australia’s reluctance to give France any kind of preferential tariff status. A constant theme in following years is his repeated advice that Australia should be signing a Trade Agreement with France. This did not happen until late 1936, and during the greater part of the early 1930s, the two countries were engaged in a veritable trade war which resulted in a significant decrease in overall trade between the two countries. Voss lamented this, and unfailingly drew attention to it. He was a faithful believer in Hughes’s vision for a greatly increased commercial relationship between Australia and France, and for twenty years he did everything he could to keep that dream alive through the work of the Paris office. Against him, he had the inertia of the long-standing Australian economic policy of ‘protection plus preference’ (preference for Great Britain and the Empire) and the smugness of Australian politicians and officials more than content with a favourable balance of trade, and blinkered by their confidence that the sheep’s back would guarantee the nation’s prosperity for the foreseeable future. Nonetheless, through his careful and caring networking with French business and political figures, and his knowledge of, and sensitivity to, French ways of doing things, Voss was respected by the French as a worthy and reliable interlocutor.

Beyond the commercial sphere, Voss worked tirelessly to facilitate the travels of hundreds of Australian visitors to France—he was in fact the official representative of the Australian National Travel Association. Among these visitors would have been many on the painful pilgrimage to the grave sites of the Western Front. He was well known and well liked among travellers, surely an important contribution in developing relations between the Australian and French peoples. Furthermore, by virtue of the length of his time in Paris, he helped establish the idea of a distinct Australian official representation in France as a norm. However tenuous, the notion of an Australian relationship with France was given a tangible and enduring basis, which might not have been the case had Voss not fought so persistently to demonstrate its value.

Early in World War II, when Paris fell, Voss escaped with his family to Britain, where he was incorporated into the Commonwealth Intelligence Branch. He spent most of the war in Liverpool, managing (with what was recognised as great diplomacy and skill) the waterside and stevedoring activities needed to keep Australian wartime shipping running smoothly. During this time, in 1943, he and his wife experienced the grief of losing their younger son Michel, who, having joined the RAF, was killed in a training accident in Canada.

After the war, Voss was given, albeit it reluctantly, a position as commercial attaché in the newly opened Australian Embassy. He was ultimately acknowledged, at the time of his retirement, as a ‘valuable member of staff’—a somewhat understated appreciation of a man whose career had spanned eleven Australian prime ministers and governments of every political persuasion, and who had toiled for over thirty years to keep Australia in the French consciousness. He was honoured both by the French, as chevalier de la Légion d’honneur, and by the Queen, with an MBE of which the citation praised him for ‘services in connection with the development of commercial relations between Australia and France’. Having retired to his long-time residence in Clamart, he died at the Necker Hospital in Paris on 17 August 1959 at the age of 71.

Image: Clive Voss in 1932, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

Author: Colin Nettelbeck, Emeritus Professor University of Melbourne, November 2018

References:

Hudson, W. J., 1974, Billy Hughes in Paris: the Birth of Australian Diplomacy, Melbourne, Nelson, in association with the Australian Institute of International Affairs.

National Archives of Australia, Clive Voss Files:

A461 0323/1/7 Part 1 Australian Commercial Representation – France – Appointments – Voss – Personal File

A2 1920/2849 Trade Reports by Voss CH re trade in France

A981 FRA 37 France – Misc. Letters from C. H. Voss

A981 TRAD 50 PART 1 France: Correspondence with CH Voss

A2910 442/21/8 Part 2 Mr. Clive Voss – Personal File (May 1919 to May 1930)

A2910 442/21/8 Part 3 Mr. Clive Voss – Personal File (June 1930 to April 1937)

A2910 442/21/8 Part 4 Staff – Mr Clive Harold Voss (August 1937 to December 1943)

A2910 442/21/8 Part 5 Staff – Mr Clive Harold Voss (August 1937 to December 1948)

A2910 442/21/8 Part 6 Staff – Mr Clive Harold Voss (1948 to February 1953

Schedvin, Boris, 2008, Emissaries of Trade: A History of the Australian Trade Commissioner Service, Barton, ACT, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Selected TROVE sources (in chronological order):

The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, 6 May 1911, 6.

The Bathurst Times, 23 September 1913, 1.

The Brisbane Courrier, 29 October 1931, 8.

The Sun (Sydney), 10 May 1930, 8.

Arrow (Sydney), 28 October 1932, 24

Daily Advertiser (Wagga Wagga), 1 July 1937, 6.

Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative, 27 June 1940, 10.

Daily Advertiser (Wagga Wagga), 8 July 1941, 2.

Keywords:

Voss, Australian trade with France— history, origins of Australian diplomacy, First World War aftermath, French Australian relations, 1918–19 French Economic Mission to Australia, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade